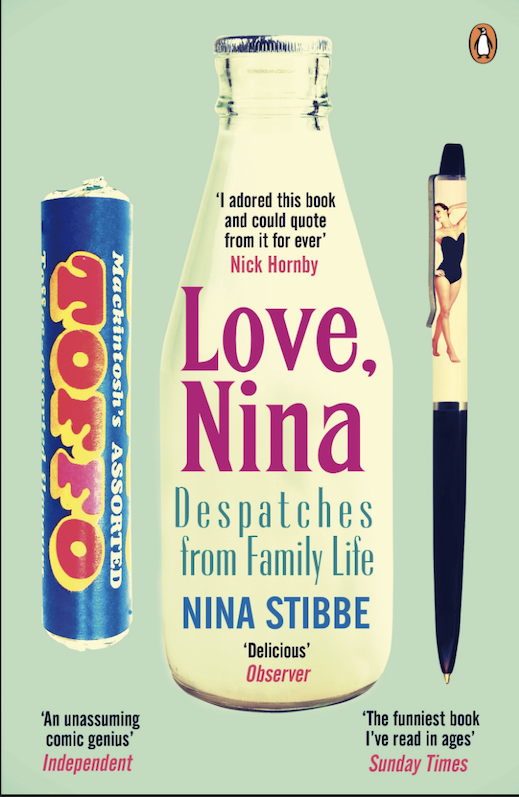

I’ve been watching a series called Love, Nina on the ABC. It’s based on a book by Nina Stibbe about her early days as a nanny working for a single mum (played by Helena Bonham-Carter) in a somewhat bohemian household in London.

Bonham-Carter plays Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the London Review of Books, who Stibbe worked for as a young woman. Nick Hornby wrote the script, and it’s very amusing, especially the dialogue between the two boys and their mum. There’s also an odd neighbour (a Scottish poet) who comes to their house for dinner every night and constantly criticises Nina’s cooking.

In the series Nina moves from Leicester to London and discovers ‘literature’ because of her friendship with a young man who lives three doors up. Early in the series he sees her reading Shirley Conran’s Lace, a trashy novel popular in the 1970s, and gives her a copy of The Return of the Native (Thomas Hardy), but she finds it frustrating and impenetrable. There’s a delightful scene where she’s reading it to her nine-year-old charge and pretending that it’s Enid Blyton so that he can help her understand what it means, but he sees through her plan and demands that she reads him The Famous Five instead.

Eventually Nina realises Hardy is writing about the characters’ interior life and not just documenting their everyday activities. She marvels at the idea that everyone has an interior life, even Aunty Gladys, and that this is what literature is all about.

I’m not sure whether this is true, and to be honest I have read little Hardy since I was about 17, but I have noticed that when you go into a bookshop, there’s always a shelf labelled ‘literary fiction’, and one labelled ‘fiction’ or sometimes ‘general fiction’. Sometimes there’s another shelf called women’s fiction, but never a shelf called men’s fiction. Poor men, why don’t they get a shelf?

Writer and teacher Allison K Williams says that in simple terms, a literary book is just one that has sold less than 10,000 copies, but I think there’s more to it than that (and I think she’d agree). She is merely making the point that if you are planning to write literary fiction, then you’d better not expect to sell thousands of copies unless you win the Booker Prize or another big literary award. Commercial fiction is written with the market in mind, and the big publishing houses seem to think that most people want to read books that are just like other books. That’s why you see books marketed as the new Eleanor Oliphant, for example.

The dictionary defines ‘literature’ as written work that is considered superior or has lasting artistic merit, but I’m not sure who decides these things. Some books are more thoughtful and engaging than others, and these are the ones that I like to read, regardless of the label.

I’m keen to know what things mean, and perhaps be moved to think about wider themes such as the value of friendship, honesty, and love, but I think these ideas can be explored in a well plotted murder mystery or a romance novel. In order for a book to move me there needs to be something that resonates at a conscious, or perhaps unconscious level, but I’m not bothered if it’s also a page-turner. I like complex characters and long sprawling multi-generational books, but most of all, I like strong storytelling.

I like books that stay with me after I’ve finished reading them. Sometimes I even catch myself wondering how the characters in the book are going, as if they were actually friends or people I’ve met somewhere. I like flawed characters and dislike one-dimensional goody two shoes. People who are good all the time are just not realistic in my book. Who’s nice all the time in real life? Not me, that’s for sure.