When a new person subscribes to Book Chat, I like to check out what other content they share on Substack. I think of it as audience research. It helps me understand what they are interested in, but I often feel sad when I see people who seem perpetually angry and outraged, sharing content that amplifies these feelings, rather than sharing anything uplifting or positive.

I worry about the mental health of people who are deeply engaged in the latest outrage cycle, whether it’s politics, AI doom-scrolling, or manufactured controversy. As an Australian, I’m particularly unmoved by American political drama, but the pattern is universal: people trapped in loops of indignation.

I rarely watch or listen to the news. I like knowing what’s happening in the world, but I can’t bear how the press sensationalises stories or presents only one side. Over the years, I’ve realised that constant exposure to negative news and political commentary only makes me angry and has no impact on the outcome.

I do believe in protest—both public and private—when it matters. But sharing outrage on a continuous loop isn’t good for you or your circle of friends. And every minute you spend on negative social media posts tells the algorithm you want more doom and gloom.

That’s why my feed is full of rabbits, cats, dogs, book recommendations, and recipes. I also get posts about cosy home renovations. Sometimes I even see updates from actual friends. I quite enjoy checking my social media feed because I’ve deliberately curated it to show me uplifting stories.

Research confirms that excessive bad news raises anxiety and cortisol levels and disrupts sleep. Covid proved this dramatically.

But what about genuine emergencies? Recently, the Central Coast experienced a devastating bushfire that destroyed 12 local homes. We were safe but concerned about friends and the wider community. In situations like this, staying informed is necessary—yet the constant news reports, sirens, and helicopters created intense unease.

The South Australia Health Service offers this advice for protecting your mental health during crises:

- Manage your exposure. Take frequent breaks from news and social media. Choose one reliable source and stick with it instead of channel-hopping.

- Maintain basic self-care. Eat well and prioritise sleep.

- Allow yourself to feel. Anxiety during crises is normal. Be kind to yourself.

- Connect and contribute. Feeling helpless increases anxiety. Reach out to friends, check on neighbours, or ask someone how they’re doing. Small actions help.

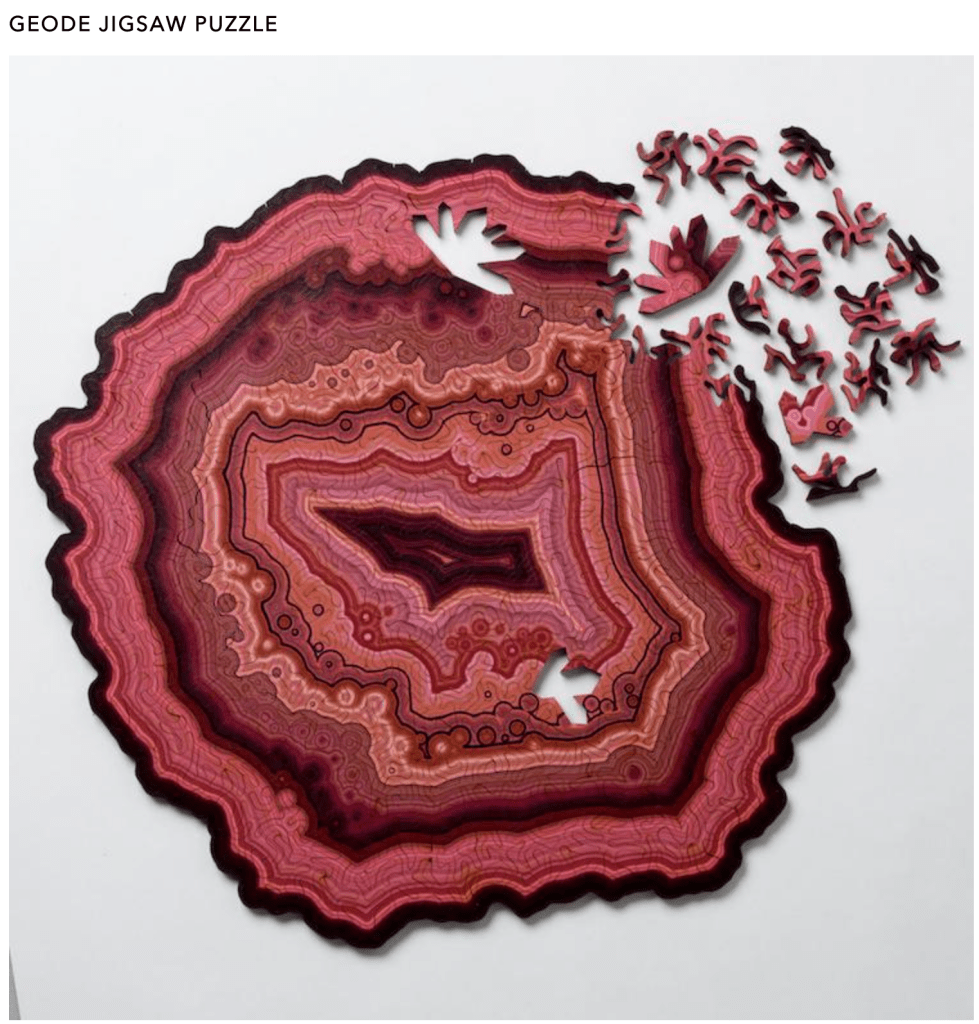

- Focus your mind. Practice mindfulness, meditation, or absorbing activities like crafting, cooking, or reading. Light entertainment works better than anything too demanding.

- Listen to music. If your concentration skills are low, try listening to some soothing music or anything that makes you feel good.

The goal isn’t ignorance—it’s balance. Stay informed when it matters, but protect your mental health the rest of the time. Fill your feed with puppies and rabbits. You’ll be better for it.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like Comfort Reading

Find out more about BOOK CHAT here.